The Search for Samuel

The first rule of genealogy is to research backwards systematically, confirming what you know and always looking for clues to the unknown. Some ancestors kindly appear in records just where you might expect them and it is easy to get birth, marriage and death certificates, which in turn probably point to their parents. The biggest risk for these ancestors is that you might forget to look for interesting stories along the way.

Other ancestors, like Samuel Etherington, required me to search far and wide in less obvious records. The result was that I learnt a lot more about him than if he had been easier to find.

Family

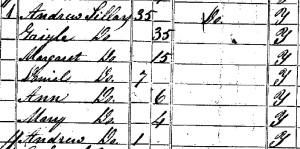

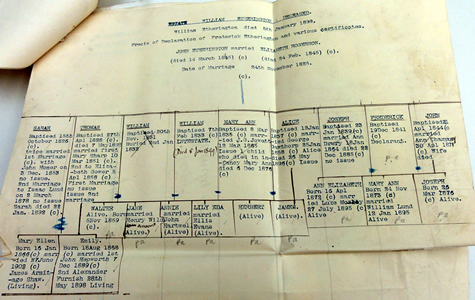

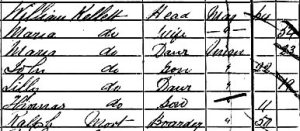

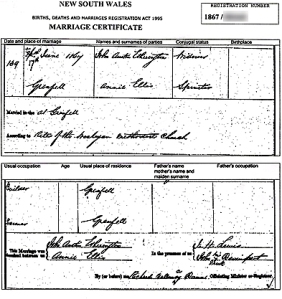

My mother’s grandfather was William Edward Etherington. I found his marriage to Annie Barbara McNeill (in Surry Hills, Sydney),1 his marriage certificate listing his parents as Samuel Etherington and Sarah Everett, but I could not find his birth certificate. Eventually I found his baptism, which listed his parents as Samuel and Sarah Etherington, living at King St, Sydney.2 Samuel was described as a ‘cabinet maker’.

Unable to find a marriage record for Samuel, I turned to researching other children of Samuel and Sarah, hoping that in those records there might be further clues. For son John I could find a marriage but no birth registered. John’s marriage certificate named his father as Samuel Etherington, a baker.3 I did find a baptism for daughter Emmeline,4 which listed her father as Samuel Henry Hetherington, an engineer, living at Miller’s Point. (Cabinet maker, baker, engineer?)

(Samuel’s daughter) Harriet’s baptism certificate listed her father as an engineer.5 On Harriet’s marriage certificate, her father was listed as a commercial traveller.6 Samuel’s son Alfred died at only 16 months old. On his baptism, Samuel was listed as an engineer.7 On Alfred’s death certificate, Samuel was listed as a carpenter.8 On the marriage certificate of another son (Frederick), Samuel was described as a clerk.9

On all these records, Samuel’s wife was named as Sarah (née Everitt or Everett). Sarah had been baptised at St John’s in Limerick City in Ireland10 and migrated with her parents to Sydney in 1841.11 I could not find a marriage between Samuel and Sarah, but when Sarah died in 1885, she was described as a widow.12

Timeline

Samuel’s origins remained a puzzle – I could not find a record of either his birth in, or immigration to, Australia. In the absence of further family records, I turned to building up a timeline of his addresses and occupations. Some of these details were listed in the birth or marriage certificates of his children, but others came from directories, such as the Sydney, Suburban and Country Commercial Directory, published by John Sands.13 Electoral rolls also provided addresses and sometimes occupations.14 Samuel was variously listed as: an engineer, a builder, a carpenter or cabinet maker, a clerk, a commercial traveller – before the surprising shift to baker.

Other Etherington families?

Fortunately Etherington was not such a common name in Australia, so I began building up family trees of anyone in Australia named Etherington or Hetherington, hoping for clues. As well as birth, death, marriage and address records, I also searched newspapers – made much easier when the wonderful Trove website came online.15 Among its many collections, Trove contains easily searchable digitised newspapers. In researching all the family, the marriage announcement for son John mentioned that Samuel was ‘late of London’.16

I decided to extend my search to Etherington families in south-east England, starting with those who had a family member come to Australia. I was hoping for maybe a sibling called Samuel in England who might have disappeared from English records.

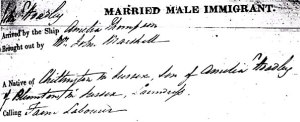

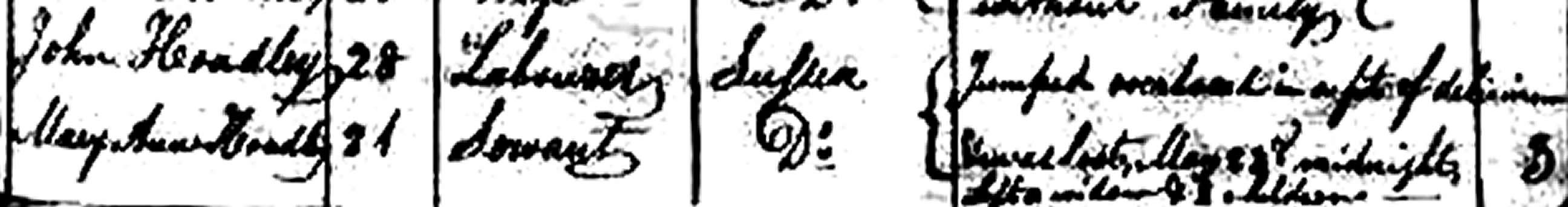

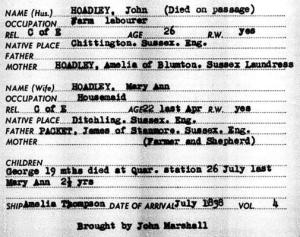

In 1857 Thomas and Ann Etherington arrived in Sydney.17 Searching in the indexes of the NSW State Archives collection (Museums of History NSW website) I found two microfilm numbers associated with their arrival in Australia as Assisted Immigrants.18 The first film contained the information Thomas and Ann provided when they boarded the ship in England, and this has been digitised. The second microfilm contains information collected by the Immigration Board when Thomas and Ann disembarked in Sydney. This second microfilm was not digitised and I viewed it at the State Archives Reading Room. In addition to the information collected in London, the Immigration Board in Sydney also asked immigrants to give details of their parents. Thomas said that his parents were ‘Joseph and Henrietta, mother dead, father living at Peckham’.

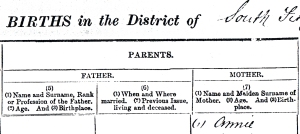

Thomas and Ann had been married in London before travelling together to Australia.19 Thomas was the son of Joseph Etherington, a builder, and Ann was the daughter of John Etherington, also a builder. In the 1841 English census, I found Thomas living in Southwark (just south of London) with his parents Joseph (a carpenter) and Hetty.20 Also listed in the family were Thomas’ six siblings – including his older sister Anna. Further researching this family, I found that Anna had been baptised in 1824 – on the same day as an older brother Samuel.21

I could not find record of a marriage or death for this Samuel, so I wondered if he might be the Samuel Etherington I was seeking?

In those early days of the Internet, I posted enquiries about this family wherever I could. Might there be someone else researching the Etherington family in NSW or else the family of Joseph and Hetty/Henrietta Etherington of Southwark, England? Eventually I received this reply:

Are you looking for information about Samuel Etherington, who married Hester Holmes in England about 1836 and came to NSW? His mother’s name was also Holmes. They used the name Holmes instead of Etherington in Australia. Samuel died in Bombala in 1903.

This exciting reply gave me more research clues – as well as contact with a descendant of Samuel’s sister Anna. Anna’s son had written to the Lloyd’s Weekly newspaper in London in 1903, and that enquiry was re-published in Australian newspapers:

Hetherington (Samuel) landed in Sydney, N.S.W., in 1838, last heard of in 1888, trading as S. Holmes, Steam Flour Mills, Sydney. Sister Anna’s son inquires.22

Samuel’s son had written back, and Anna’s descendant still has that letter.

Dear Sir, Mr. H.S. Holmes, Tocumwall, New South Wales, Australia, says his father, your uncle, traded for many years as a flour miller under the name of Holmes. He died in Bombala, N.S.W. in April last year. Please let us know if you will write to your cousin.

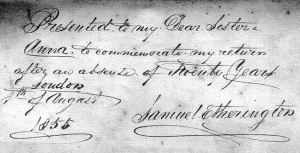

Anna’s descendant also still has the prayer book that Samuel inscribed and signed and gave to his sister when he visited London in 1855.

With all this information, I started researching NSW miller and baker Samuel Holmes.

While Samuel Etherington was in England visiting his sister, the wife of Samuel Holmes gave evidence at a trial for one of his employees, and noted Samuel’s ‘temporary absence in England’.23

In 1858 Samuel Holmes gave evidence at an enquiry into the quality of flour in Sydney, and mentioned that he had examined the manufacture of flour in Richmond, Virginia ‘about two years ago’.24 That led to discovering that while Samuel Etherington had visited his sister Anna in England, it was as Samuel Holmes that he travelled home to Australia via North America.25

I tracked the names Samuel Holmes and Samuel Etherington through directories and NSW electoral rolls, gradually adding to the timeline of his addresses and listed occupations associated with both names.

In 1860 a fire broke out in Samuel Holmes’ bakery and mill in King Street, Sydney. The bakery was adjacent to the Prince of Wales Theatre, and the fire not only destroyed Samuel’s business, but also that theatre.26 Two months later Samuel Holmes wrote to the Sydney Council, requesting a reduction on his water rates, given that he was not currently using water in his business.27

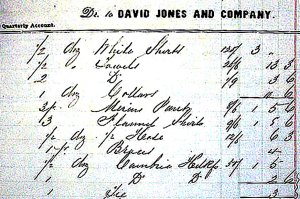

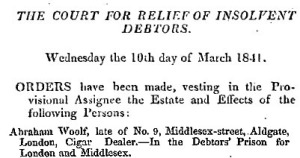

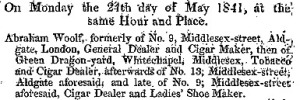

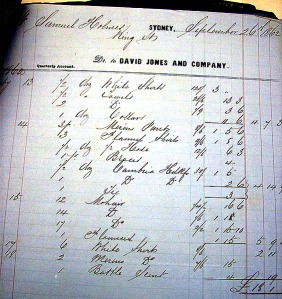

Samuel Holmes was declared insolvent several times during his business life (in 184828, 186229 and 187130) before finally being declared bankrupt in 1891.31 The file associated with his 1862 insolvency gives great insights into his life, including a David Jones (department store) bill that he was unable to pay. Perhaps Samuel was planning to re-outfit himself following the fire.

Doves’ 1880 map of Sydney32 shows that Samuel Holmes rebuilt his bakery and flour mill adjacent to the newly rebuilt theatre (renamed the Theatre Royal). Once again patrons entered the stalls of the theatre through Samuel’s bakery.

Volume 2 of The Aldine Centennial History of New South Wales includes biographies of ‘prominent inhabitants’.33 As chairman of the Master Bakers Association, Samuel Holmes is included. This notes that his bakery is ‘the largest as well as the oldest house of the kind in Sydney’ undertaking ‘baking, steam biscuit making and steam flour milling’. Apparently his business also supplied electric light to the Theatre Royal, as well as ‘to light with electricity from the corner of Pitt-street up King-street and round to the new arcade in Castlereagh street’.

I found an illustration of Samuel’s earlier bakery in the Rocks area of Sydney in 1848, in the building that had formerly been the offices of the Sydney Gazette.34 35

In 1897 a newspaper reported that Samuel Holmes had become proprietor of the Bombala Roller Flour Mill.36 In the leadup to Australia’s federation (1901), Bombala was one of the places being considered as a potential national capital. Samuel is mentioned again when there was an attempted robbery of his Bombala house in 1903.37

Finally the death of Samuel Holmes was reported, in Bombala on 10 April 1903.38 His son Henry Holmes was the informant on Samuel’s death certificate, which mentions a second family, but ‘details unknown’.39 Samuel died intestate, leaving more in debts than assets.40 He was buried in an unmarked grave in Bombala Cemetery.

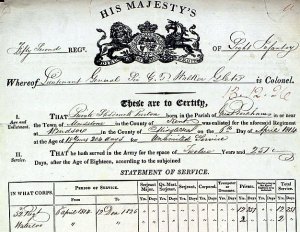

When I searched for Samuel’s arrival in Australia, using the clue that his nephew had mentioned (1838), still nothing was simple. Samuel Holmes arrived on the ship Alfred on 31 December 1837. He was described as an ‘unmarried male immigrant’ aged 18 (in fact he was 15) with occupation given as ‘baker and farmer’, and with native place listed as Weeley in Essex.41 On that same voyage was an Ellen Holmes, listed as an unmarried 25-year-old dress maker, also from Weeley.

When Hester Holmes died in Sydney in 1879, the informant on her death certificate was her ‘husband’ Samuel Holmes of King Street. Her parents were listed as John Holmes, a baker, and Sarah Erith.42 In looking at Weeley baptisms, the daughter of John Holmes and Sarah (‘formerly Erith’) was baptised as Helen Holmes.43 So Helen (or Ellen) Holmes became Hester Holmes and Samuel Etherington called himself her husband, Samuel Holmes.

DNA testing and comparison with descendants of the children of the various siblings of Samuel (and also his cousins) have confirmed the above conclusions.

The following timeline puts the story in order.

SE refers to records in the name of Samuel Etherington – SH means in the name of Samuel Holmes.

| 1822 | SE born Southwark, England | baptism21 |

| 1837 | SH arrived Sydney | immigration41 |

| 1840 | SH son Henry Holmes born | Henry’s death cert47 |

| 1842-1857 | SH Holmes children Ann, George, Henrietta born | all died young44 45 46 |

| 1848 | SH journeyman baker, Glebe Sydney | Insolvency28 |

| 1848 | SH baker Miller’s Point, Sydney | Fowles34 |

| 1850-1852 | SH bread & biscuit maker, King St, Holmes children Thomas & Emma | both died young 48 49 |

| 1853 | SH baker, King St | court case50 |

| 1855 | SE in London | visiting sister23 |

| 1855 | SH returns from England to Australia via USA | flour inquiry (Trove)24 passenger list25 |

| 1857 | SE son Samuel Joseph Etherington born | 51 |

| 1858 | SH baker, King St | directory52 |

| 1860 | SH fire in King St bakery | 26 |

| 1859-1866 | SE Etherington children Emmeline, John, Harriet, Arthur born | 3 4 5 |

| 1867 | SH baker AND SE cabinet maker, King St | SH directory53 SE birth son WIlliam2 |

| 1868-1873 | SE children Alfred, Frederick born | 7 8 9 |

| 1876 | SE baker, Buckingham St | marriage of son51 |

| 1879 | SH Hester Holmes died | 42 |

| 1885 | SE Sarah (née Everitt) died | 12 |

| 1886 | SE commercial traveller | marriage of daughter6 |

| 1891 | SH bankrupt | 31 |

| 1897 | SH proprietor of Bombala Flour Mill | 36 |

| 1903 | SH Samuel died in Bombala | 38 39 |

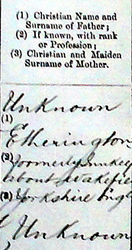

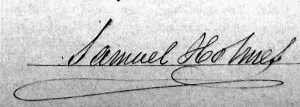

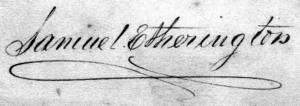

The signatures in the names of Samuel Etherington and Samuel Holmes provide further evidence that this was in fact the same person.

References

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1891/1380, marriage of William E Etherington & Annie McNeill.back

- Ancestry.com, Sydney, Australia, Anglican Parish Registers, 1814-2011 William Edward Etherington born 16 Feb 1867, baptised at St Andrew’s Sydney on 2 Aug 1867.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1909/3385, marriage of John H Etherington.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, 8286/1859 V18598286 121C, baptism of Emmeline Emily Hetherington.

- Ancestry.com, Sydney, Australia, Anglican Parish Registers, 1814-2011 Harriett Martha Hetherington born 27 Nov 1864, baptised at St Andrew’s Sydney on 19 Jun 1865.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1886/211, marriage of Harriet Etherington.

- Ancestry.com, Sydney, Australia, Anglican Parish Registers, 1814-2011 Alfred Henry Etherington born 8 Sep 1868, baptised at St Andrew’s Sydney on 27 Nov 1868.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1870/89, death of Alfred Henry Etherington.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1894/402, marriage of Frederick Charles Etherington.

- “Ireland Births and Baptisms, 1620-1881”, database, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FRQK-58Q : 5 February 2020), Sarah Everett, 1830.

- “Australia, New South Wales, Index to Bounty Immigrants, 1828-1842”, database with images, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:FL29-SWP : 13 June 2019), John Everitt, 1841.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1885/1597, death of Sarah Etherington.

- City of Sydney Archives, Sands Postal Directories, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/495003.

- Ancestry has some relevant electoral rolls at New South Wales, Australia, Historical Electoral Rolls,1842-1864 at https://www.ancestry.com.au/search/categories/auvoters/ but many more are available at the State Library of NSW.

- https://trove.nla.gov.au/, hosted and published by the National Library of Australia.

- 1876 ‘Family Notices’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 1 August, p. 1. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13377536.

- Museums of History NSW, Assisted Immigrants Index 1839-1896, Reel 2138, [4/4794]; Reel 2475, [4/4967], https://search.records.nsw.gov.au/primo-explore/fulldisplay?context=L&vid=61SRA&lang=en_US&docid=INDEX867787 and https://indexes.records.nsw.gov.au/ebook/list.aspx?series=NRS5316&item=4_4794&ship=Boanerges

- https://mhnsw.au/indexes/immigration-and-shipping/assisted-immigrants-index/.

- General Register Office UK, the marriage of Thomas Etherington and Ann Etherington was registered in the June quarter 1857 at West London, volume 1c page 118.

- Ancestry.com, 1841 England Census, Joseph Etherington, Class: HO107; Piece: 1087; Book: 9; Civil Parish: St Olave; County: Surrey; Enumeration District: 2; Folio: 23; Page: 39; Line: 12; GSU roll: 474669.

- Ancestry.com, London, England, Church of England Births and Baptisms, 1813-1923 for Anna Etherington, London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P71/JN/016.

- 1903 ‘KITH AND KIN.’, The Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 – 1955), 16 October, p. 2. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article80963308.

- 1855 ‘CENTRAL CRIMINAL COURT—MONDAY.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 4 December, p. 4., http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article12978754.

- 1858 ‘THE SYDNEY MORNING HERALD.’, The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), 28 June, p. 4. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13018015.

- Ancestry.com, New York U.S., Arriving Passenger and Crew Lists, 1820-1957 for Samuel Holmes, Year: 1855; Arrival: New York, New York, USA; Microfilm Serial: M237, 1820-1897; Line: 7; List Number: 963.

- 1860 ‘GREAT FIRE, AND LOSS OF LIFE.’, Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875), 4 October, p. 8. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60499372.

- City of Sydney Council Archives, Letters Received, CSA078183, A-000292829, No. 806, Letter received from Samuel Holmes of King Street, dated 4 Dec 1860.

- Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Insolvency Index 1842-1887, Samuel Holmes, NRS-13654-1-[2/8821]-1787.

- Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Insolvency Index 1842-1887, Samuel Holmes, NRS-13654-1-[2/9058]-5888.

- Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Insolvency Index 1842-1887, Samuel Holmes,

NRS-13654-1-[2/9415]-10451. - Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Bankruptcy Index 1888-1929, Samuel Holmes,

NRS-13655-1-[10/22724]-3979. - City of Sydney Council Archives, Plans of Sydney (Doves) in 1880, Box CSA 058395, Map 5, Block 17, Alt. ID 41, A-00880148.

- Morrison, W. F. The Aldine Centennial History of New South Wales illustrated, volume 2, Sydney, Aldine Pub. Co., 1888, reproduced at https://www.textqueensland.com.au/item/book/28ee0733e1498b7bdbf4e46d9209415c.

- Fowles, J, Sydney in 1848, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks06/0600151h.html#p14.

- Joseph Fowles, From the collections of the State Library of New South Wales, Dixson Library Q84/56],(Opp p.17 (detail), ‘Sydney in 1848 : illustrated by copper-plate engravings of its principal streets, public buildings, churches, chapels, etc.’ from drawings by Joseph Fowles) https://dictionaryofsydney.org/media/62885.

- 1897 ‘Bombala Items.’, Delegate Argus and Border Post (NSW : 1895 – 1906), 18 March, p. 4. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article109705030.

- 1903 ‘An Unpleasant Awakening.’, The Wingham Chronicle and Manning River Observer (NSW : 1898 – 1954), 21 February, p. 8. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article168027389.

- 1903 ‘No title’, Bombala Times and Manaro and Coast Districts General Advertiser (NSW : 1899 – 1905), 10 April, p. 2. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article134132596.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages 1903/5311, death of Samuel Henry Holmes.

- Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Intestate Estates Index 1821-1913, HOLMES Samuel Henry, INX-53-6110, File no 454, Previous System No [10/27658], Index no 53.

- Museums of History NSW, State Archives collection, Miscellaneous immigrants index 1828-1843 HOLMES Samuel, INX-55-4374, NRS 5313, Item No [4/4780] page 30.

Also Ancestry.com.au, New South Wales Assisted Passenger Index, taken from State Records Authority of New South Wales; Kingswood New South Wales, Australia; Persons on early migrant ships (Fair Copy); Series: 5310; Reel: 1286. - NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages #1765 in 1879, death of Hester Holmes.

- Essex Records Office, baptisms at St Andrew’s Weeley, image 19, D/P 407/1/3, baptism of Helen Holmes, child of John & Sarah, late Erith.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, death in 1847 of Anne Holmes, aged 5 years, # 229/1847 V1847229 32B, daughter of a baker.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, death in 1852 of George Holmes, aged 8 years, at the home of his parents in King St, # 663/1852 V1852663 38B, son of a baker.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, death in 1860 of Henrietta Holmes, aged 13 years, at the home of her parents in King St, registration # 602/1860, daughter of a baker.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, death in 1912 of Henry Samuel Holmes, aged 72 years, at Bombala, registration # 9584/1912.

- Sydney Early Church Records, microfilm # 993964 (C. of E. baptisms, marriages, burials, 1852-1853 (vols. 38-39)), Parish records for St James, Sydney, Thomas Holmes, born 18 Jan 1850 at King St, Sydney, baptised 1853 at St James, Sydney, son of a Samuel Holmes and Hester, father a baker, seen at the Society of Australian Genealogists.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, birth in 1852, baptism in 1853 of Emma Holmes, registration # 72/1852 V185272 39A.

- 1853 ‘SYDNEY POLICE COURT—TUESDAY.’, Empire (Sydney, NSW : 1850 – 1875), 26 January, p. 3. , http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article60137814.

- NSW Registry of Births, Deaths & Marriages, marriage of Samuel Joseph Etherington, registration # 711 in 1876.

- Sands Commercial Directory for Sydney, 1858, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1898994, page 163.

- Sands Alphabetical Directory for Sydney, 1867, https://archives.cityofsydney.nsw.gov.au/nodes/view/1898988, page 100.

DNA Painter “Cluster Auto Painter”

I’m just playing with the new tool on DNA Painter – ‘Cluster Auto Painter’. I have created MyHeritage clusters for the DNA test results of my Mum & her brother – for both I have a lot of unknown matches. I generated the DNAPainter clusters map, using information generated from ‘AutoClusters’ and ‘Segment info’ on MyHeritage. (Good instructions are given on the DNAPainter site as to how to obtain this information.)

(You need a paid subscription to DNAPainter to have multiple ‘profiles’ or different chromosome maps. A ‘free user’ would have to delete one chromosome map in order to generate another.)

Looking at the results of the ‘Cluster Auto Painter’ tool, when I know how I am related to a match, I can define the cluster including that match as maternal or paternal, and possibly also assign the cluster to the ancestral couple who handed down that DNA.

When all matches in a cluster are unknown to me, I may still be able to define the cluster as maternal /paternal if one of the matches contains an overlapping segment of sufficient size with a match I’ve already worked out. If they appear to lie in the same place on the same chromosome, do the two matches match each other? If so, then they are (probably) either both maternal or both paternal. If it looks like the segments lie on the same place on the same chromosome but the two matches do not match each other, then one must lie on the maternal chromosome of the pair while the other must lie on the paternal chromosome.

Be aware of the threshold (minimum number of centiMorgans to be counted as a match) set on the chromosome browser (eg on MyHeritage). If two segments appear to only slightly overlap there might not be more cM shared than the threshold, so both the matches could be eg maternal but not counted as matching in that location.

I started doing this DNAPainter ‘Cluster Auto Painting’ for my Mum’s matches & could identify almost all her clusters to at least maternal or paternal. Then I used that information in the cluster map created for her brother’s DNA & was able to assign the remaining clusters.

It’s possible there are other connections (between my family and the unknown match) down other lines that I have not yet explored, so “deductions based on deductions” might lead to some errors, but I have been able to at least provisionally assign my maternal MyHeritage matches to which (of my) maternal grandparents handed down that DNA – and in some cases to an ancestral couple further back.

I don’t know Mum’s maternal grandfather. From Ancestry matches I have identified a few people as definitely on that line. Fortunately a couple of those also have their DNA test on MyHeritage, so I can use this to further define some of the clusters.

The DNA Painter ‘Cluster Auto Painter’ tool does not currently work on Ancestry matches because of the latter company’s not providing matching segment information, but I’m planning to explore how much of the information I work out about MyHeritage matches can be useful in further defining clusters from the other sites that can be input into the ‘Cluster Auto Painter’ on DNAPainter.

Autosomal DNA

Autosomal DNA is inherited by both males and females and received equally from each of our parents.

In commercial genetic genealogy tests our autosomal DNA is compared against a large database of others, looking for identical segments of inherited DNA that may indicate we have shared ancestors.

Some questions that might be answered by an autosomal test include:

- Can I find previously unknown cousins, solely from my DNA?

- Can I look for relatives on all branches of my pedigree (not just my father’s patrilineal or my mother’s matrilineal lines)?

- Can I test the accuracy of the family tree I have constructed?

How does it work?

Autosomal DNA tests examine 22 of the 23 pairs of chromosomes that we inherited from each of our parents. The remaining pair (called the ‘sex chromosomes’) determines gender. (X-chromosome analysis is often also reported in autosomal tests.)

We inherit about half our autosomal DNA (atDNA) from each of our parents and so about one quarter from each of our grandparents (and an eighth from each of our great grandparents…) – eventually we may not have enough DNA from a particular ancestor to be recognisable.

Close relatives share large segments of atDNA that each has inherited from a recent ancestor in common. More distant relatives may carry smaller sections of identical DNA. Commercial DNA testing companies predict the approximate relationship between genetic cousins based on the size and number of shared identical segments of autosomal DNA. (Very small pieces of atDNA in common are more likely to be coincidental rather than inherited.)

Because of randomness each time autosomal DNA is passed on, even siblings do not have identical autosomal DNA inherited from their parents and the amount of atDNA shared between relatives can vary greatly. As the amount inherited from a particular ancestor diminishes over the generations, eventually two distant cousins may not share enough DNA for a commercial test to identify them as genetic relatives.

While first and second cousins (and closer relationships) should be recognised in an autosomal test, and third cousins are extremely likely to be identified, only around half of fourth cousins will be found by their atDNA. By the time of fifth cousins, only about 10-15% will be recognised and by sixth cousins, only about 2-5% will be identified as genetic relatives.

Because of this, the general rule of thumb is that best results from autosomal DNA tests occur when there is up to about 5 generations back to the shared ancestor. For those hoping to prove relationships beyond third cousins, it may be necessary to test more siblings or first cousins on one side (or both) in order to find a recognisable shared segment of inherited DNA.

Because of this ‘number of generations’ limitation, in autosomal tests it is better to test the oldest living family member (or the one who is in the earliest generation).

What do autosomal DNA test results look like?

The commercial companies’ autosomal tests generally report your matches in the database (and their contact details) with predicted relationships based on the amount of shared autosomal DNA.

Three main companies provide autosomal tests for genetic genealogy. Family Tree DNA calls their autosomal test ‘Family Finder’. 23andMe call their atDNA test ‘Relative Finder’. AncestryDNA also provides autosomal DNA testing.

Family Tree DNA and 23andMe also provide information about the location and size of shared segments.

Currently AncestryDNA does not provide any such chromosome information, directing those who test to look at the public trees of their matches, in the hope that shared ancestors can be recognised. ‘DNA circles’ link people who match DNA and who also have the same ancestor in their family trees.

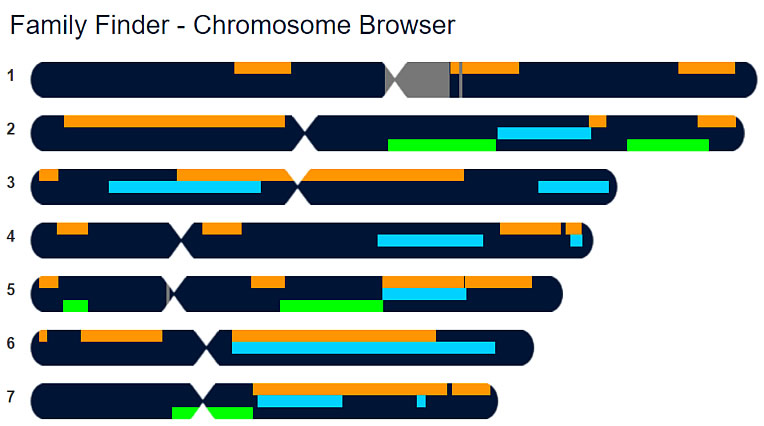

Family Tree DNA and 23andMe provide ‘chromosome browsing’ tools, showing on which chromosome/s lie any shared segments. Because the test alone cannot distinguish which chromosome was inherited from a mother and which from a father, these chromosome maps appear as images showing only one of each pair of chromosomes. For instance, in the image below the background (dark) chromosomes are mine, and the segments I share with three close relatives are shown overlaying, in different colours.

FamilyTreeDNA: chromosome segments I share with 3 close relatives, compared to my own chromosomes

Simplifying to only showing each pair as a single chromosome means that it might appear as if I match two people in the same area of the same chromosome but maybe I match one on the chromosome inherited from my mother and one on the chromosome inherited from my father. The two predicted genetic relatives may each match me but not each other. I should ask each to check if the other appears in their list of matches.

When a segment is shared between three or more people (meaning at least two besides myself and where each person also matches the others at that same location) then we share the same ancestor – this is called triangulation.

From the websites of all three companies (FamilyTreeDNA, 23andMe and AncestryDNA) one can download the raw autosomal test data in order to upload it to third party sites such as GEDmatch – which provide more tools for chromosome analysis as well as finding matches with those who tested with the other companies.

Admixture predictions are also based on autosomal DNA. Genetic admixture means the interbreeding of mixed population groups represented by our ancestors. This tends to be reported in a summary such as ‘30% British, 20% Northern European, …’. In fact this analysis is based on comparisons against databases which were probably created for other purposes than genealogy and the conclusions may not be accurate.

23andMe call their admixture analysis ‘Ancestry Composition’. Family Tree DNA calls theirs ‘My Origins’. AncestryDNA calls their admixture analysis ‘Genetic Ethnicity’. While these analyses might be interesting, the conclusions are not yet completely reliable.

What to do with the results?

Include in your profile information with the companies the surnames in your ancestry and where those ancestors lived. Contact others likely to be close relatives based on their autosomal testing – starting with those whose surnames or locations you recognise – or where some clue points to the relevant part of your ancestry. You may be able to identify where previously unknown genetic relatives fit into your family tree. Then you can begin to share photographs and information in the same way as with more traditional genealogical methods.

You can also test known second or third cousins in order to identify which portions of DNA you share with them, that must have been inherited from known ancestors, and then see if those same segments are also shared with potential matches identified in the database. This might help identify to which branch of the family a new suggested genetic relative belongs.

By testing the DNA of known relatives, you can also check the family tree you have constructed, to see whether DNA confirms the expected relationships.

Autosomal DNA provides another tool that genealogists can use to find relatives and prove relationships. Its benefit is that it is not restricted to a single line (patrilineal or matrilineal) but instead relates to all branches of our ancestry. Its limitation is that it might not be able to identify relatives with a shared ancestor more than about five or six generations earlier.

DNA from our mother’s mothers

This article discusses the DNA we all inherit from our mother’s mothers (our matrilineal line). This genetic material is called mitochondrial DNA or mtDNA for short.

Mothers pass mtDNA to all their children but only their daughters pass it on – largely unchanged – to the next generations. Your mtDNA was only inherited from your mother and she inherited it from her mother – and so on – back through the generations. Everyone (male and female) can test mtDNA and compare our mtDNA with others. Those who match us share a direct maternal line ancestor.

Family historians often find it difficult tracing female ancestors because women traditionally changed their surnames with marriage. As DNA does not concern itself with surnames, genealogists can use mtDNA testing as another tool to find maternal ancestors, in conjunction with other more traditional family history research methods.

Some questions that might be answered by a mtDNA test include:

- From what (general) region did my maternal line come?

- My great grandfather married twice. Am I descended from his first or second wife?

- Can I find other people also descended from the same direct maternal line to help my search for my female ancestors?

How does it work?

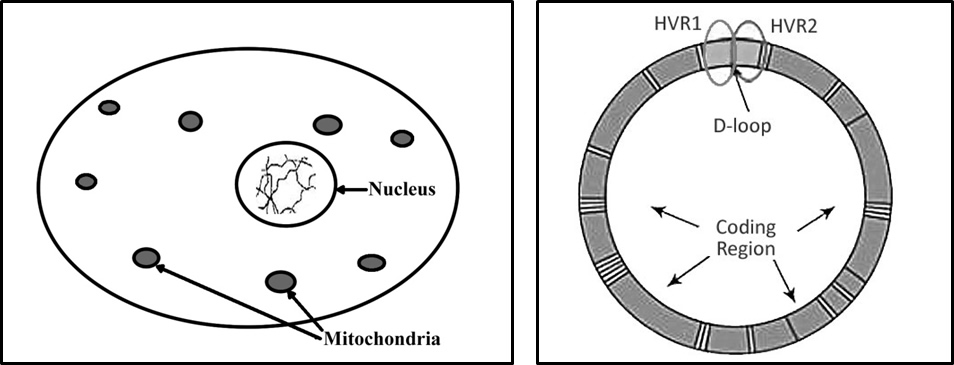

Human cell Ring-shaped mitochondria

Other DNA tests examine the 23 pairs of chromosomes that we inherited from each of our parents. Such chromosomes are found on the double helix shaped strands inside the cell’s nucleus. Mitochondria are quite different– they lie outside the nucleus, are approximately ring-shaped and also contain DNA.

Mitochondria also carry variations caused by copying errors that occurred in the past when cells copied mtDNA to pass on to the next generation. Such mitochondrial mutations occur only very rarely so large groups of population share much of their mtDNA.

The first commercial mtDNA tests only examined small areas of the ring (HVR1 and HVR2) which together make up the D-loop area of mtDNA. Matching someone on HVR1 and HVR2 does imply a shared maternal ancestor but that ancestor possibly lived hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

In recent years Family Tree DNA has offered a Full Mitochondrial Sequence test (FMS) of the entire mitochondrial ring – including the Coding Region. Exact matches in a full sequence test share a maternal ancestor who probably lived within a genealogical timeframe – that is, in recent enough generations that we may be able to identify her in our family trees.

What do mtDNA test results look like?

A group of scientists examined and sequenced all the mtDNA of one individual and published those results in 1981. They named those results the Cambridge Reference Sequence (or CRS). A corrected version (sometimes referred to as the revised Cambridge Reference Sequence or rCRS) was published in 1999.

When I have my mtDNA tested, companies report to me where my mitochondrial DNA differs from the standard (rCRS). For each of the areas HVR1, HVR2 and Coding Region I am told the small number of differences that my mtDNA has from the rCRS. I can assume that for any locations not reported, I have the same result as the standard.

My results also include my mitochondrial haplogroup, which provides a summary statement of my DNA and mutations, indicating where I fit into the mitochondrial genetic tree of all humans.

Commercial mtDNA tests also report to me other people who have tested with the same company whose DNA closely matches my own. A ‘genetic distance of 0’ indicates that in the areas we have each tested (HVR1, HVR2 and maybe Coding Region) my mtDNA is exactly the same as that of my match. A ‘genetic distance of 1’ means that there is 1 difference between us – and so on.

Which company to use?

Family Tree DNA is the only company that currently offers a full sequence test of mtDNA for genealogical purposes. They call that test mtFull Sequence or FMS. Family Tree DNA often has sales when significantly discounted prices are available. (The company’s Facebook page is one way to learn about such sales.)

Family Tree DNA also host projects based on mtDNA geographic origins and also mtDNA haplogroups. Projects are managed by knowledgeable volunteers who analyse the similar DNA of large groups of people in order to draw further conclusions.

Joining such projects is free and you can usually join any that might be of interest – such as for those whose maternal ancestors came from a particular geographic region. Once you discover your mtDNA haplogroup, I recommend you also join the relevant mtDNA haplogroup project – others in these projects share maternal heritage, even though they do not share surnames.

What to do with my results?

We all have mitochondria inherited only from our direct maternal line (although only females pass that mtDNA on to their own children). Family historians can look for others who share ancestors with us on that matrilineal line.

In addition, genealogists can consider any female of interest in their family tree and follow her female lines forward through her daughters’ daughters and on to (either gender) in the current generation. By testing the mtDNA of other living family members, we can also look for their mtDNA matches.

I do not try to identify shared ancestors with anyone who has only tested HVR1 or HVR2. Any shared maternal ancestors might have lived thousands of years ago. However if I match exactly with someone who (like me) has tested the full sequence of mitochondria, we have about a 50% chance that our shared maternal ancestor lived within around 150 years and a 90% chance that the shared ancestor lived within about 400 years. In other words, our shared maternal ancestor may have lived recently enough to be found in our family trees.

Because testing of the full sequence of mtDNA has only been commercially available in very recent years, far fewer people have taken that test than (for example) males have tested the DNA of their direct paternal line. So currently the chance of finding someone who shares direct maternal ancestors with us is still small. However as more people take a full sequence test of mtDNA, our chances of finding others related to us on our direct maternal line will increase. As a family historian, I look forward to anything that will help me find my female ancestors and those related to me on that line.

Using Y-chromosome DNA

DNA testing does not provide names and so is not a substitute for more traditional family history research techniques. However a genealogist can use DNA testing as another tool to answer some family history questions in the absence of other documents.

Some questions that might be answered by a Y-chromosome (Y-DNA) test include:

- Another man with the same surname lived near my ancestor. Were they related?

- I think my female ancestor had a lover (or a second husband). Can I determine which man fathered her son?

- My grandfather was adopted. I have a theory about who might be his father, can I prove it?

- Can I prove that he and his brother are sons of the same man?

Father-to-son inheritance

Y-chromosome DNA (or Y-DNA) is a particular type of genetic material that is passed largely unchanged between a father and his son. As such, comparing the Y-DNA between two men can answer questions about whether they shared ancestors on the all-male line.

A female like myself who wants to answer the same sorts of questions needs to find a willing male close relative to be tested. I have ordered Y-DNA tests for my father, his mother’s nephew and also my mother’s brother in order to examine my nearest male lines.

In theory Y-DNA follows the path of surname inheritance and so finding a close Y-DNA match with another male who has the same surname is a good indicator that those men share an ancestor.

There are many reasons why a surname might not have been inherited along with Y-DNA. Geneticists refer to these as ‘non-paternity events’, when the father is either unknown or not the person commonly believed. A Y-DNA test could confirm a theory about paternity even when the possible father and son have different surnames.

To look for relationships between men long dead I need to find a living male descendant (down all-male lines) from each of them.

Sometimes that means stepping sideways – for example, researching a brother’s line if some man in the line had no male descendants. In other words, it is necessary to combine the use of more traditional family history research techniques with the new information offered by DNA.

A male with no clue about their father could take a Y-DNA test to learn which surnames occur most frequently amongst their genetic relatives and use these names as possible clues. (Alternatively a different DNA test – an autosomal test – might locate a cousin and that might help identify the father.)

I have also had serendipitous discoveries, when someone who tested with the same company was identified as a Y-DNA match with one of my family and we were able to identify the shared ancestor. Thus I have discovered previously unknown cousins, allowing an exchange of information about family history.

How does it work?

Every cell in your body has 23 pairs of chromosomes, inherited from your parents. The 23rd pair are the sex chromosomes – males have an X- and a Y-chromosome while females have two X-chromosomes. Note that only males have a Y-chromosome.

In each generation the Y- chromosome (or Y-DNA) of the father is copied (largely unchanged) in order to be passed on to his sons. However occasionally cells make a copying error.

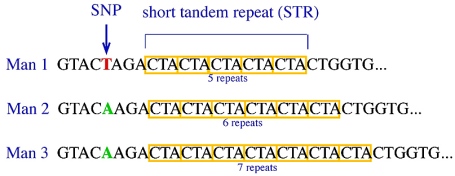

Sometimes the number of repeats of a group of DNA ‘letters’ (called a short tandem repeat or STR) is increased or decreased.

The other mutation occurs only very rarely, when a single DNA ‘letter’ is miscopied (rather like a typo) – this is called a single nucleotide polymorphism (or SNP, pronounced ‘snip’). As both these changes are then transferred to future generations, the Y-DNA becomes rather like an audit trail, recording inheritance on the direct paternal line.

These mutations are illustrated in the diagram below. In the example Man 1 is the father of Man 2. When the Y-DNA of Man 1 is being copied, a SNP occurs when a ‘T’ is accidentally miscopied as an ‘A’. This change is inherited by Man 2 who then passes it on to his descendants.

Man 1 also has a segment of DNA with a short tandem repeat (STR) where the ‘letters’ CTA are repeated 5 times. We say that Man 1 has a repeat count (or allele) of 5 at that point. When that repeating section was copied for passing to Man 2, the number of repeats was increased – so 5 repeats became 6 repeats. By the time that DNA was re-copied and passed to their descendant Man 3, those 6 repeats have mutated to become 7 repeats. Note that Man 3 also continues to carry the ‘A’ variation of the SNP inherited by Man 2.

Inherited mutations (from www.le.ac.uk/ge/maj4/NewWebSurnames041008.html)

A genealogical Y-DNA test reports on certain STRs on the Y-chromosome. Rather than checking the whole chromosome, a male can order a Y-DNA test of certain useful sections of DNA (or markers) – currently available tests examine between 12 and 111 markers. When the repeat counts at those markers are compared against those of another male, a close match indicates that the two men share an ancestor on their all-male or patrilineal line. Depending on how closely they match, an estimate can be made about how many generations earlier their most recent common ancestor (or MRCA) probably lived.

Genealogists should test at least 37 markers. Anything less and it could be that an indicated shared ancestor lived many hundreds or even thousands of years ago.

Genetic genealogy tests also examine the SNPs (‘typos’) on the Y-chromosome. Such SNPs indicate the haplogroup – or where the male tested fits into the broad family tree of all men.

Which company to use?

The US company Family Tree DNA is the main company offering specific STR marker testing of the Y-chromosome with the required level of accuracy required by genealogists as well as having a large database of others’ Y-DNA results for comparison. This company offers tests of between 37 and 111 markers as well as tools to interpret the results. For under US$170 (at the time of writing) it is possible for males to test their Y-DNA with sufficient accuracy to determine whether two men are likely to share a common ancestor ‘within a genealogical timeframe’ and also receive an estimate about how many generations ago that shared ancestor lived.

You can save money by ordering the Y-DNA test through a surname-specific project. Projects are managed by knowledgeable volunteers who analyse the similar DNA of large groups of people in order to draw further conclusions. By looking at the DNA of enough people with the same surname, it may be possible to identify when a particular mutation occurred. For example you may learn that ‘all those with this particular mutation descend from one brother but those without that mutation descend from the other brother’.

Many projects focus on a common surname but there are also geographic and ethnic heritage projects. Joining projects is free and you can usually join any that might be of interest – such as for other surnames that occur frequently among your DNA matches! Once you discover your Y-DNA haplogroup, I recommend you also join the relevant haplogroup project – those matches share Y-DNA heritage, whether or not they share surnames.

Family Tree DNA often has sales when significantly discounted prices are available. (The company’s Facebook page is one way to learn about such sales.)

Websites

Family Tree DNA

Projects on Family Tree DNA

Webinars on Family Tree DNA

Family Tree DNA on Facebook

Ysearch (for those who have tested with another company and want to compare their results against the Family Tree DNA database)

Introduction to using DNA with your family history research

Traditional family history research involves looking for documents that name an ancestor – and hoping that everybody told the truth! By contrast, genetic tools that are now available to genealogists tell the truth but do not name ancestors – however they can be used to find relatives and to check the accuracy of our constructed family trees.

Why use DNA testing?

I have an ancestor who was adopted. When I eventually located his original birth certificate, no father was named. I developed a plausible theory about who his father might have been, but I could not find any record to prove or disprove my idea.

In another case my ancestor, John Etherington, a builder, sits at the top of one of my ancestral lines but I cannot find any documentary evidence that he was related to the John Etherington, also a builder, who lived two streets away. Another ancestor, Samuel Etherington, was reputed to also be the Samuel Holmes who fathered another family. To solve puzzles such as these I needed a different set of genealogical tools.

What is DNA testing?

Genetic genealogy testing is all about comparing our DNA with others. Closer relatives share more DNA in common with us than more distant relatives. Genetic genealogy tests examine the areas of DNA where we differ – and predict approximately how closely we are related.

Sometimes we have a particular theory to check and we know in advance the two individuals we wish to compare. At other times genealogists are ‘fishing’ in the DNA ‘nets’, hoping to find unexpected genetic matches who might share an ancestor with us and who might then have information about unknown family branches. In the latter case there are benefits in comparing with as many people as possible. One way to do this is choosing a company with a large database of other people already tested.

DNA testing companies

Currently the main options for genealogists looking for living genetic relatives are the three US companies Family Tree DNA, 23andMe and AncestryDNA (a branch of Ancestry.com).

- Family Tree DNA is the company chosen by most genealogists – and these tend to respond to family history enquiries. Moreover this company’s website has useful tools available for comparing DNA as well as recorded webinars freely available.

- 23andMe offers genetic health predisposition reports as well as ancestry information. Many of their customers chose the company for those health reports and so are less interested in responding to genealogists. A dispute with the US Federal Drugs Administration (FDA) currently prevents 23andMe from providing health reports to new customers except in the United Kingdom and Canada.

- AncestryDNA tests were released first to US consumers and so most of the people in their database are in the United States. Recently AncestryDNA began offering tests to Australians. AncestryDNA test results can be linked to Ancestry trees.

Ordering a test involves going to the company’s website, selecting a test and paying by credit card and then the kit will be posted to you. Family Tree DNA and AncestryDNA tests involve swabbing inside your cheek (with something like a toothbrush) – in the way we have seen on television crime shows. The 23andMe test involves filling a test tube with saliva. In either method customers then post their completed kits back to the company and some weeks later are advised by email when their results are available online. Customers log on to the company’s website with a userID and password to find their results and matching customers predicted to be genetic relatives.

Which test should I take?

DNA testing is advancing (as well as becoming cheaper!) and so is more available for checking theories about your family history and perhaps even breaking down brick walls you might currently face. This article introduces the options currently available that might be useful to family historians.

Test 1: Y-chromosome tests, for males to test DNA inherited from their father’s fathers

For under US$200 we can test whether two males are likely to share a common ancestor ‘within a genealogical timeframe’, and how many generations ago that shared ancestor probably lived.

This test is valid for any two men who might share a male ancestor – they do not need to have the same surname. When testing with a company that has a huge database of people already tested, I might find a match with some living descendant who shares with me a common ancestor. This is useful for all genealogists but perhaps especially for adoptees.

I have used this test to discern whether two families with the same surname were actually related to each other, in the absence of documentary proof. I have also used this test to check (and refute) a theory about who might have been the biological father of an adopted male. It was necessary to find a living male descendant (down an all-male line) from the adopted male and also to find a living male descendant (down an all-male line) from the hypothesised birth father, and then compare the DNA that each inherited from their father’s fathers.

Y-chromosome tests are only available to males, as only males have a Y-chromosome. Females like me need to ask a near male relative to be tested – a brother, father, or uncle. I have ordered tests for my father and also my mother’s brother in order to examine my nearest male lines. For Y-chromosome tests, I recommend using the company FamilyTreeDNA and testing at least 37 markers.

Test 2: Mitochondrial tests, for anyone to test DNA inherited from their mother’s mothers

Useful DNA tests are no longer limited to males. We all have a different type of DNA (called mitochondria) that we inherited from our mother’s mother’s mother. Previously mitochondrial DNA could only tell us about ancient ancestors and their migratory patterns, but now it is possible to obtain much more recent information. Family Tree DNA offers a full sequence test of all our mitochondria, allowing us to identify people who share an ancestor with us on our maternal line within about 100-400 years. That test is also currently available for under US$200.

Test 3: Autosomal tests, to test the DNA inherited half from each of our parents

We are not restricted to testing only the DNA of our father’s fathers or our mother’s mothers. It is also possible to test our remaining DNA, inherited equally from both of our parents – this DNA is called ‘autosomal’. These tests compare the DNA of our ancestors regardless of gender, because we inherit half our autosomal DNA from each of our parents (and via them, from their ancestors). However as we inherit one quarter of our DNA from each of our grandparents (and so one eighth from each of our great grandparents) eventually the inherited material from any particular ancestor becomes so small as to be difficult to identify.

Consequently, when comparing this autosomal DNA with someone else, our best conclusions are when the shared ancestor lived no more than about five generations ago.

Commercial autosomal tests also report on our likely population origins or admixture, for example, ‘60% British, 20% Scandinavian and 20% Jewish’. The sample databases used for comparison are very small and currently most of these predictions are considered unreliable.

Family Tree DNA calls their autosomal test ‘Family Finder’, while 23andMe calls a similar test ‘DNA Relatives’. Both tests cost under US$100 – plus postage. (23andMe’s postage and handling charges to Australia adds another three quarters to the price of their kit!) The AncestryDNA test costs Australians under US$150 (plus postage) but if you do not have an Ancestry.com subscription there is an annual cost for accessing your results.

For any genetic relatives identified in their autosomal tests, Family Tree DNA and 23andMe also report on shared segments of the X-chromosome. Females have two X-chromosomes (inherited one from each parent) while males have one (inherited from their mother). When trying to work out which ancestral branch might have passed down the X-DNA we share with some match in the database, genealogists can look at pedigree charts and eliminate any father-to-son branches, as fathers do not pass any X-chromosomes to their sons.

Use the tests in conjunction

The tests can also be used in conjunction. The autosomal ‘Family Finder’ test through Family Tree DNA identifies matches with my DNA and calculates a likely relationship.

One of my matches (described as a possible 3rd to 5th cousin) seemed to have very similar Y-chromosome (father’s father’s) DNA to my mother’s brother. I made contact and by swapping names of grandparents and their parents we soon identified that he was the son of a 3rd cousin to me (and so indeed within the range of 3rd to 5th cousins).

Autosomal testing can be used to check your constructed family tree.

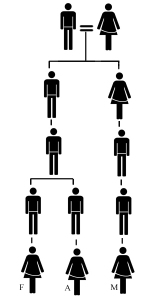

Comparing the autosomal DNA of the three female cousins (Fay, Ann and Maureen) at the bottom of this diagram confirmed my constructed family tree of their relationships back to their shared ancestors.

(Spouses omitted after the first generation to simplify the diagram.)

Conclusion

It is not necessary to understand how a car works in order to drive it, but it is necessary to know the functions of driving. In the same way it is unnecessary to understand much about the science of DNA – but it is necessary to understand what sorts of questions can be answered by the different DNA tests so you can use them as tools to aid your family history research.

The most recent DNA tests available to genealogists offer useful information which can supplement traditional genealogical methods. Family trees are still needed to identify ancestors and draw conclusions about relationships. DNA tests can supplement this genealogical research, filling in gaps in the paper trails. With such tools we can test our conclusions and assumptions in constructed family trees by confirming or disproving reputed relationships. As more people are tested and databases grow, commercial DNA tests are even more likely to help us find relatives that we might not have found by traditional methods.

Australian & NZ births, deaths & marriages

The earliest records available in the new colonies were the church records of baptisms, marriages and burials. Many people are missing from these registers – not all records have survived and not everybody had a church ceremony (especially in those places where initially only the Anglican Church was recognised).

In due time, governments needed better records of the people in the colony, so they introduced government-administered registration of births, deaths and marriages – or civil registration. District registrars were appointed and information was reported to them. In an age where many people were illiterate, registrars had to guess how to spell the names. (Remember this when searching for names in indexes – often the reason for not finding someone is because of spelling variations.)

Church ceremonies continued to take place, so it may be possible to obtain a copy of the information collected by the church, as well as the corresponding civil certificate.

As a general rule, the government asked for more information on civil certificates than was contained in the corresponding church record – but sometimes the opposite is true. For example, NSW marriage certificates (especially in the 1860s and 1870s) may not include information such as parents’ names and occupations, even though such information might be found in the corresponding church record.

As English and Welsh civil registration began on 1st July 1837, the earliest Australasian colonies to issue civil certificates (of birth, death and marriage) followed the English model:

- Birth registrations asked for the child’s name, date and place of birth and the names of the parents

- Marriages registrations asked for the couple’s names, ages, residences and occupations and sometimes details of the fathers

- Death registrations included questions about the deceased’s name, age and occupation as well as the date, place and cause of death

When the Victorian government began civil registration in 1853, they requested more information on certificates. Other colonies (and Scotland) that introduced civil registration later largely followed the Victorian practice of collecting the additional information, such as:

- Birth registrations also asked for the parents’ ages, place of birth and marriage details, and details of previous children

- Marriage registrations asked for the couple’s birthplaces and details of both fathers and mothers

- Death registrations asked for the deceased’s birthplace, parents’ and spouse’s names, marriage details, children’s names and burial place

Some or all of these additional fields of information on Victorian certificates were added in later years to the certificates of the regions that had earlier followed the English style of certificates.

Colonies that followed the English model were:

- Tasmania, earlier known as Van Diemen’s Land (from 1 December 1838)

- Western Australia (from 9 September 1841)

- South Australia (from 1 July 1842)

- Northern Territory was administered by South Australia from 1863 to 1911, so their civil BDM certificates (from 24 Aug 1870) follow the South Australian pattern

- New Zealand (from 1848) – although registration was not compulsory until 1856

The colonies that followed the Victorian model were:

- Victoria (from 1 July 1853)

- New South Wales (from 1 March 1856)

- Queensland did not separate from NSW as a separate colony until 1859, so their earliest civil certificates were issued from NSW (1856-59)

- Australian Capital Territory (from 1 January 1930) – prior to that in NSW records

Even when registration was compulsory, not all births, deaths and marriages were registered and some registrations have been lost (especially in the early years). Perhaps the parties had to travel some distance to the District Registrar, and might not have bothered. They might have distrusted the government and been unwilling to supply the information.

Even if you find the certificate, just because a question is asked, does not mean that the informant knew the answer. Under such circumstances a field might be left blank, or the informant might simply have made a guess.

For example, in NSW the parents were required to register a birth, the minister registered marriages, and it was the responsibility of the owner of a house to register a death. If the parents registering a birth were unmarried, unwillingness to admit this might lead to an invented marriage date. Similarly a young couple might lie about their ages in order to marry without their parents’ permission.

Death certificates are notorious for errors and missing information. The informant might not have known the information – the son of an immigrant might never have met their grandparents, and so might not know their names. If the death took place in a hospital or institution, the owner might not know family details. There are death certificates where even the name of the deceased is unknown.

Each state and territory has their own Registry of Births, Deaths and Marriages. There are microfiche indexes, CD-ROM indexes and sometimes online indexes. Not all indexes contain exactly the same information, and sometimes an item is missing from one index but present in another. So if you can’t find the entry in an online index, try visiting a library or genealogy society that holds microfiche and/or CD-ROM indexes.

For privacy reasons there is restricted public access to ‘recent’ certificates of births, deaths and marriages. Each state or territory determines their own definition of ‘recent’. Generally more restrictions have been put in place for online indexes than existed at the time of the earlier microfiche and CD-ROM indexes. So if you can access these earlier indexes, you may be able to search more recent indexes than are available online.

When searching indexes, always ensure you write down reference numbers for records of interest, as certificates may be cheaper with reference numbers supplied. For NSW and South Australia it is possible to obtain transcriptions more cheaply than certificates. (Such transcriptions are not legal documents, but as they include all the information on the certificates, they may be suitable for genealogical purposes.)

Victorian online indexes cost to search, however it is possible to obtain a copy as an unofficial ‘historic document’ more cheaply than an official certificate. For New Zealand, obtaining a ‘printout’ of the information on a post-1874 document is cheaper than obtaining a standard certificate.

(This article was written for findmypast.com.au)

These days many of the Australian births, deaths and marriages can be searched on Ancestry.com.au and South Australian and Northern Territory BDM indexes are also available on findmypast.com.au.

- Links to Australian indexes of BDM & transcription agents

- Contact details for Australian Registries of BDM, and costs of certificates (Cora Num)

- Available Australian BDM indexes (Cora Num)

- See also my blog post on BDM certificates & saving money

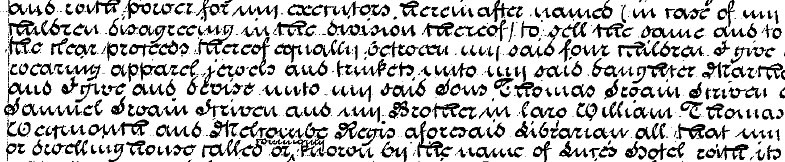

Tracing Jewish ancestors, from London to Amsterdam

I’ve written previously about how I visited the archives and museums in Poznan and Leszno (Poland) looking for further information about my ancestors (Samuel and Isaac SHUTER, sons of Michael) before they migrated to London in 1848.

A recent episode of the TV show ‘Who do you think you are?’ (about actress June Brown) prompted me to look again at ancestors who came to London from Amsterdam – in particular Joseph MYERS. I’d seen books that included hundreds of years of Dutch Jewish records, but at that time I didn’t know how the Anglicized names I was seeing might have appeared in Dutch records.

Harold Lewin’s book (‘Marriage Records of the Great Synagogue London 1791-1885’) has been of great assistance in identifying the marriages of my ancestors in London. For most of the 18th, 19th and even early 20th century, the Great Synagogue in Duke’s Place London was the main synagogue for Ashkenazi Jews (those who came from German and Eastern Europe, as opposed to the Sephardic Jews who came from Spain and Portugal). Because of the use of patronymic names, Jewish records contain not only details of the bride and groom, but also their fathers, and often addresses and sometimes ages. Because the Great Synagogue was the main place of worship for so long, families can be traced back over several generations, perhaps eventually identifying the original family member who migrated to London.

[For those unable to see Harold Lewin’s book, Angela Shire also compiled a book ‘Great Synagogue Marriage Registers 1791-1850’ which might be more readily available and is also available through Amazon.co.uk. Shire’s book has a little less information per entry but additional cross-indexing, when compared to Lewin’s book.]

My 4xgreat.grandfather Joseph MYERS married Rebecca COHEN at the Great Synagogue in London in 1819. From the UK census of 1851, I learned that he was born in Amsterdam, probably around 1792. Harold Lewin’s book provided his patronymic name of Yosef Yozpa b. Shmuel Halevi – Joseph Juzpa, son of Samuel the Levite. Joseph’s sister Anna was enumerated with him in the 1851 and 1871 censuses – records show that she had been born about 1795 in Amsterdam. [In Shire’s book he is given as Joseph Yozefa s. of Shmuel HaLevi.]

That was as much as I knew for many years, until recently I decided to have another look for Joseph in the Dutch Jewish records – and hopefully online.

I found the wonderful website called Dutch Jewry and within that the Ashkenazi Marriage database and the ‘Ashkenazi in Amsterdam’ database.

The Amsterdam Municipal Archives possess a complete set of registers of intended marriages from 1578 to 1811, the year when the present Civil Registry was started. Between 1598 and 1811, 15238 Jewish couples were entered in these books. (http://www.dutchjewry.org/tim/jewish_marriage_in_Amsterdam.htm)

The compilers of the online Ashkenazi in Amsterdam database have gathered together records of circumcisions, marriages, cemetery records and more, grouped into families – allowing researchers like me easy access to information held in a place I cannot easily visit and written in a language I could not read. I still might not have found my ancestor, except that I sent an email to the owners of the site, giving the information I had and asking for advice. I received a very helpful reply identifying that my Joseph Juzpa MYERS, son of Samuel, was likely to be the same person as Joseph Juzpe Kapper, son of Samuel Meyer Kapper – who previously had the family name of Levie-Drukker (Levie referring to ‘of the Levite tribe’ and ‘Drukker’ meaning ‘printer’). When the family had been naturalized in 1811, they adopted the surname Kapper (meaning ‘barber’).

According to those Dutch records, Joseph Juzpe was born 26 January 1793, of parents Samuel Meyer (Kapper) and Mariana Gans. The Dutch records confirmed that his sister Anna was born in 1795 in Amsterdam, and he also had brothers Joseph (probably deceased young), Simon, Meyer, Mozes and Nathan. So far I have followed the Dutch records back on some lines to my 9xgreat.grandparents. It’s not all just ‘names and dates’ either – there are fascinating detailed glimpses of family members in other records.

Zeeburg Cemetery, Amsterdam

I haven’t yet finished following my ancestors through all the available information, but apparently at least one of the families came originally from Hamburg to Amsterdam and another from Frankfurt, so there are clear directions about where to look next for earlier generations.

World War 1 centenary projects

Recently I’ve spoken to a number of people involved in projects researching those who enlisted for World War 1. As the centenary of WW1 approaches, the many commemoration projects seem to be running largely in isolation.

Recently I’ve spoken to a number of people involved in projects researching those who enlisted for World War 1. As the centenary of WW1 approaches, the many commemoration projects seem to be running largely in isolation.

Some projects are run in conjunction with local libraries, with volunteer researchers adding information to local studies collections. Other projects aim to produce CDs or books to be sold.

The lack of coordination between the various projects could lead to overlapping of people of interest. Someone might have been born in Mosman, but lived in Ryde at the time of enlisting – and so both areas’ projects might flag the individual as someone to be researched. Indeed that individual may even appear on the war memorial in yet another location, if a family member contributed the soldier’s name to their local war memorial.

When research resources are scarce, it makes sense for there to be some coordination between the projects to identify which individuals are being researched and in which resources. How best to do this? Local studies librarians’ networks allow sharing information about their projects, but what about projects not coordinated by libraries?

One possibility might be adding a small notice onto the Mapping our Anzacs website, which allows submissions of scrapbook entries. Obviously anyone can contribute photos or research about the lives of family members, but it would also be possible to add a scrapbook post that says something like ‘This individual is being researched by the Mosman 1914-18 project – further information can be found at …’

Thus whether the information gathered in research is intended to be freely available at a library or website, or even sold in a commercial publication, anyone interested in that WW1 participant would be directed to further information. Also the various project coordinators could make informed decisions about whether or not to proceed with researching an individual already being considered as part of another project.

‘War memorials in NSW’ includes a spreadsheet of summary information about names on particular memorials. The various projects could consider adding information to those spreadsheets, and also add details of additional memorials to those already included on the site.

Those involved in the various projects should also be aware of the Australian Government Anzac Centenary funding grants and publicity.

What other projects are you aware of?

(My handout for researching World War 1 participants can be found here.)

Passenger lists leaving UK

The following is a blog post I wrote for findmypast.com.au. It appeared on 30 July 2012.

It’s a common experience for genealogists – tracking ancestors forward through the UK censuses – to find that suddenly the whole family seems to vanish from the records. Eventually it might occur to us to wonder, did they migrate somewhere? If so, where did they go?

This is where the collection ‘Passenger lists leaving the UK 1890–1960’ on findmypast.com.au can be so useful. These are the digitised and indexed lists of passengers embarking on long-distance voyages made from all British ports (England, Scotland, Ireland and Wales). If the ship stopped en route at additional ports, such as in Europe, passengers disembarking at those stops are also included. The original documents are held in The National Archives UK in series BT 27 (BT = Board of Trade). Findmypast has indexed together all departures from all British ports, allowing researchers to enter their ancestor’s name of interest and determine the destination.

The most common way of searching for immigrant ancestors is to search the archives of the destination country. But which government archives to check? In the case of passengers to Australia, the individual colonies (and then states) administered immigration separately until 1922, after which immigration control became a function of the Commonwealth Government. (A further complication when looking for immigration records is that, just as today, immigration is typically handled at the first port of call.)

Using findmypast.com.au, there is a better way. Look under ‘Travel & migration’ and select the record set ‘Passenger Lists Leaving the UK 1890-1960’. I was searching for the migration of my grandmother, Olwena KELLETT, who was born in Lancashire in 1901. I entered her name (with first name variants) and searched between 1901 and 1907. It is a free search – not even requiring a subscription to do the search.

I selected ‘name variants’ – which also allows for the fact that some passenger lists only identify people by an initial. I found her in 1905, where she travelled from Britain to South Africa.

The above information is as far as you can go with a free search. It requires a subscription or PayAsYouGo credits to see the transcription of the results or full image of the page. The amount of information available on the passenger lists varies widely over time. Some only have minimal information about the passengers, while others include their dates of birth, occupations, and addresses in Britain before departure as well as their ultimate destinations overseas.

I had already found the record of the family’s arrival in Australia, and had assumed they had travelled on that same ship from London to Sydney. But instead little Olwena travelled with her mother to South Africa first, and then 2 years later the family travelled on to Sydney.

As many of the passenger indexes available in Australia concentrate on ships that came from British ports, ancestors who travelled first to places like South Africa or North America might not be included in the indexes of arrivals in Australia. Looking instead at the departures from Britain might help us understand what happened.

Just as today, not every person travelling was an immigrant. Apart from the seamen, many of our ancestors (such as merchants) travelled for work and people travelled for holidays. Families who had already migrated travelled back to Britain to visit family and friends. In other words, a surprising number of our ancestors appear in passenger lists crossing the oceans. Using the indexes of passengers leaving Britain provides a very useful additional way of tracking their journeys.

DNA tools for genealogists

DNA technology is advancing so rapidly that it is difficult to keep abreast of the advances and possibilities. Moreover rapidly falling prices make genetic testing more affordable and so more accessible. Here are some current options:

Test 1: Y-chromosome tests, for males to test DNA inherited from their father’s fathers

It is now possible for under US$200 for males to test the DNA they have inherited from their father’s father’s fathers, with sufficient accuracy to determine whether two men likely share a common ancestor ‘within a genealogical timeframe’ and how many generations ago that common ancestor probably lived.

I have used this test to discern whether two families with the same surname were actually related to each other, in situations where I have not yet found documentary proof. I have also used this particular DNA test to check (and finally refute) a theory about who might have been the biological father of an adopted male. It was necessary to find a living male descendant (down an all-male line) from the adopted male and also to find a living male descendant (down an all-male line) from the hypothesised birth father, and then compare the DNA that each inherited from their father’s fathers.

DNA is not related to surnames and so I am not restricted to testing two men with the same surname – the test is valid for any two men who might share a common male ancestor. However when I order this test, if I choose to use a commercial testing company like Family Tree DNA – which has a huge (and growing) database – I might find in their database a match with some living descendant who shares a common ancestor that I did not know about. This is especially useful for adoptees.

The above DNA test is only available to males (as only males have a Y-chromosome). Females like me need to ask a near male relative to be tested. I have asked my father and also my mother’s brother to be tested – this opens up for examination my nearest male lines.

Test 2: Mitochondrial tests, for anyone to test DNA inherited from their mother’s mothers

Useful DNA tests are no longer limited to males. We all have a different type of DNA (called mitochondria) that we inherit from our mother’s mother’s mothers. Mitochondria mutates so slowly that formerly the only conclusions we could draw from our maternal line was about ancient ancestors and their migratory patterns.

However that is no longer true. The company Family Tree DNA offers full sequence tests of all our mitochondria (DNA that is inherited from our mothers) that allow us to identify people who share an ancestor through our mother’s mother’s mothers, within about 200 years. [Thank you Bill Hurst for pointing out that while 23andMe also tests the ‘coding region’ of our mitochondria, they do not test or give results for all 16,571 locations, so theirs is not in fact a full sequence test.]

When the above matrilineal full sequence tests first became available, they cost close to $1,000. That price has dropped now to under US$300 (sometimes under $200).

Test 3: Autosomal tests, to test the DNA inherited half from each of our parents

We are not restricted to testing only the DNA of our father’s fathers or our mother’s mothers. Since 2010 it is possible to test the remaining nuclear DNA (that is, not the sex chromosomes). This DNA is called autosomal. Family Tree DNA calls their autosomal test Family Finder, while 23andMe calls a similar test Relative Finder. (Again these tests are under US$300 and sometimes under $200.)

These particular tests can check the DNA of our ancestors regardless of gender, because we inherit about half our autosomal DNA from each of our parents (and via them, from their ancestors) and this DNA can also be compared with the DNA of others. However as we inherit about one quarter of our DNA from each of our grandparents (and so about one eighth from each of our great grandparents) – eventually the inherited material from one particular ancestor becomes so small as to be difficult to identify definitively. Consequently, when comparing this autosomal DNA with someone else, our best conclusions are when the common ancestor lived no more than about 6 generations ago.

Use the tests in conjunction